Two Quite Recent Biographies Of Christopher Marlowe.

Original Source Of The Shakespeare-X Message.

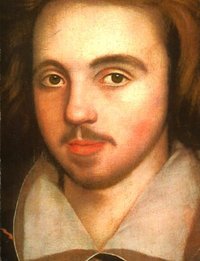

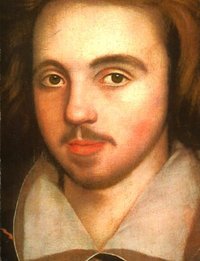

Shakespeare-Marlowe in 1585 at age 21.

André Carrilho

Shakespeare-Marlowe in 2009 at age 445.

Two Recent Biographies of Christopher Marlowe:

Park Honan: Christopher Marlowe, Poet & Spy

David Riggs: The World Of Christopher Marlowe

Park Honan: Christopher Marlowe, Poet & Spy.

From Publishers Weekly:

Park Honan: Christopher Marlowe, Poet & Spy

When it comes to the accumulation of apocryphal legend, few poets can compete with Christopher Marlowe: Scholars have long ruminated over evidence of his activities as a "spy, unceasing blasphemer, a tough street-fighter and courageous homosexual," not to mention his murder at age 29. In this well-crafted biography, Honan (Shakespeare: A Life) sheds light on the much-speculated (and previously erroneously reported) aspects of Marlowe's life without neglecting its more ordinary features (his stable two-parent upbringing, his diligent scholarship at Cambridge) or destroying the poet's aura of intrigue. Honan engages with the work of prior scholars, but draws his own conclusions, employing Cambridge University records, unpaid bills ("he still seems to have owed for lamb chops and beer"), and "suddenly acquired" documents to freshly reconstruct Marlowe's activities, which included arrests, brawls, imprisonments and his involvement in a counterfeiting operation in the Netherlands. Honan writes that "as a poet, Marlowe had interested himself in clandestine power, tricks, abasement, and immoral force," and by infusing his account with close readings of Tamburlaine, The Jew of Malta, Dr. Faustus and Hero and Leander, Honan explores the fascinating convergence of Marlowe's dual professions. Finally, revisiting the coroner's report and the facts surrounding Marlowe's final hours (he died after being stabbed in the face), Honan handles the poet's murder with the same attention to detail he brings to his life. The care and depth of this biography honor Marlowe's complexities-as Honan writes, "Our lives do not fit into the conventional genres of the stage, as he knew."

From Booklist:

Park Honan: Christopher Marlowe, Poet & Spy.

*Starred Review* The year ends as it began, with a splendid book about the man who launched the miracle that is Elizabethan-Jacobean drama. In The World of Christopher Marlowe (2005), David Riggs immersed readers in the power struggles of Elizabethan England to convince them that Marlowe's violent death wasn't out of the ordinary and that the religion-tinged political mayhem Marlowe put onstage reflected lived reality. Honan educes more of the person. For instance, whereas Riggs says there are no portraits of Marlowe, Honan allows that at least one portrait, discovered in 1952, just may be authentic. To fully conjure Marlowe's personality, Honan analyzes his great plays--the two parts of Tamburlaine the Great, Doctor Faustus The Jew of Malta, and Edward II--to reveal their heroes' psychological complexities and powerfully suggest that their creator possessed a mind as modernly sympathetic as Shakespeare's. If anything, Marlowe preferred flawed and even villainous protagonists more than Shakespeare did, and he rather encourages seeing their sins and dark deeds as reactions to a cruel and unjust world that ultimately destroys them. Honan's Marlowe, especially read in tandem with Riggs' World, makes the Elizabethan ambience palpable. Ray Olson

Street-Fighting Man

'Christopher Marlowe: Poet and Spy,' by Park Honan

New York Times

Review by Michael Feingold

January 29, 2006

PEOPLE who complain that we have so few biographical facts about Shakespeare, and use that lack of data as an excuse for indulging in fantasies about who "really" wrote his plays, should ponder the case of Christopher Marlowe (at one time a favorite candidate for that ghostwriter role), about whom even less is known. He flashed across the Tudor literary scene for a stunningly brief period, raising the standards of poetic achievement and transforming Elizabethan theater. Few pre-Shakespearean English plays still hold the stage; they include at least four of Marlowe's. In recent decades, "Tamburlaine the Great" (its two parts usually condensed into one evening), "The Jew of Malta," "Doctor Faustus" and "Edward II" have had regular revivals.

This is all the more remarkable because Marlowe (1564-93), unlike Shakespeare, is not the writer to comfort an audience with a jolly evening in the theater. A contrarian of epic stature, he's most often celebrated as an embodiment of rebellion in every form: a cynic about all received ideas of society and religion; almost certainly a homosexual; most likely a government spy; probably an atheist; possibly even a dabbler in the occult; and, to round off the list, a glorifier of violence who died in a tavern brawl. Much of the eyewitness testimony we have of Marlowe was supplied by people anxious to depict him, for their own petty reasons, as an evil influence: he is the man who supposedly said that Jesus' mother was "dishonest" and that "all they that love not tobacco and boys are fools." Among Renaissance bad-boy artists, he ranks in the top echelon, along with his equally notorious Italian contemporary, the painter Caravaggio.

The hot-blooded, wickedly sardonic rebel Marlowe, however, can be glimpsed only intermittently in Park Honan's new biography, "Christopher Marlowe: Poet and Spy." Honan, best known for his widely read "Shakespeare: A Life," has an agenda. He does not want to whitewash Marlowe (hardly possible anyway, given the evidence), but he does want to rescue his subject from the bad-boy image that makes Marlowe a figure of popular myth, and restore him to his full value as poet and dramatist. The result is a book that frustrates, and occasionally infuriates, as often as it fascinates, because at its core the myth fits the facts of Marlowe's life and art only too well, driving Honan into an apologetic swarm of digressions, speculations, half-evasions and logic-choppings. He gives a sumptuously detailed picture of Marlowe's world, but rarely brings the poet himself into focus. In its unsteady shifts from topic to topic, his work sometimes resembles one of those Renaissance miscellanies in which scholars delight: from it you can learn about Elizabethan wills, trade guilds, ecclesiastical politics, real estate deals, military maneuvers, family trees, college living conditions and every kind of courtly or legal intrigue. But when it comes to Marlowe himself, Honan buries the scant available evidence in a small forest of imagined scenes and unwarranted assumptions. "With success, Marlowe had become fonder than ever of personal display." About Marlowe and Shakespeare: "Did they meet often? Or become intimate? Plainly, no record of their talk together survives." In fact, we know nothing about Marlowe's fondness for personal display, or whether he and Shakespeare ever met.

One can't wholly blame Honan for making free with such limited materials. The information on Marlowe is so tenuous that there is uncertainty even about his last name, which appears variously in the existing documents as Marlow, Marle, Marley, Morley, Marlen, Marlin and Marlinge. The son of a debt-ridden cobbler in the cathedral town of Canterbury, Marlowe, or whatever his name was, must have shown his gift for language early on: he was granted a scholarship to the best local school and a subsequent one to Cambridge, from which he emerged after six years with an M.A. degree in 1587. By that time, Marlowe was apparently both an aspiring poet and a spy. Recently unearthed documents cited by Honan suggest he received his degree, after academic years that included long, unexplained absences, only at the intervention of the Privy Council, on grounds of his unspecified "good service" to the nation.

More than likely, this "service" involved posing as a Roman Catholic. In Tudor England, religion and politics were one: roiled by sectarian strife, the country was menaced on one side by Catholics, with support from France and Spain, and pressured on the other by Puritan extremists who viewed the official Church of England as too dangerously close to "papistry." Expatriate English colleges at Reims and elsewhere sent home streams of double agents, intending to reconvert England to Catholicism, by assassination if necessary. Elizabeth's advisers maintained an elaborate network of agents and couriers, to keep tabs on one another as well as on these infiltrators and on heretical Puritans; more than one of Marlowe's Cambridge classmates ended up martyred or in exile.

We know little of Marlowe's own activities as a spy, any more than we do about the composition of his plays or what profit he derived from their tremendous success. That they were successful is undoubted. Once produced, plays in that era were the theater company's property, kept out of print (to avoid rival productions) until they went out of use, unless demand for them was exceptional. Marlowe's effect on the public can be gauged by noting that the two parts of "Tamburlaine" and "Doctor Faustus" were both published within a few years of their production; the latter went through an extraordinary nine quarto editions by 1632.

Part of what made, and still makes, Marlowe's drama fascinating makes Honan uncomfortable. Wishing to find something in the plays besides a brute, unrepentant nihilism, he tries to present a case for Marlowe as a philosopher, struggling to analyze society and religion, and as a satirist attacking the abuse of power. This leads to some of his fuzziest writing, for the plain truth is that Marlowe is admirable exactly to the extent that he is unredeemable. The world of his plays is a vicious one, in which the temptations to attain power and, once attained, to abuse it are mankind's principal motives. No one would deny either Marlowe's analytic gifts or his darkly satiric temperament, but they are put at the service of an all-encompassing negativity. Writing for a Christian nation that lived in constant suspicion of foreigners and heretics, he finds Muslims, Jews, overt homosexuals and other outsiders marginally preferable to Christians, because their bloodlust and greed come without Christian hypocrisy attached. His superheroes are all also supervillains. ("Tamburlaine," C. S. Lewis memorably quipped, is "the story of Giant the Jack Killer.") When they die, fighting or defeated, they may regret, but never repent, their deeds.

The obvious affinity between Marlowe's bleak vision and those of our own time, from the ultraviolent Terminators and Hannibal Lecters of filmdom to the wholehearted despair of Beckett's desolate mindscapes, makes him seem, in many unnerving ways, more our contemporary than Shakespeare. Even the disheartening fixation on gratuitous cruelty in so many plays today finds an ancestor in him. Shakespeare learned from him technically, in matters of both verse and stagecraft, and was inspired by him to take risks. That he can't be equated with Shakespeare (and could not possibly have written Shakespeare's plays) is self-evident precisely because his own sensibility is so distinctive. Honan had no need to defend Marlowe's reputation from imaginary detractors. Marlowe's forthrightness proves that a bold attack is the best defense. But though his absence from his own biography is a pity, the rich, complex vision of Elizabethan life that "Christopher Marlowe" supplies can make his poetic gift for cutting to the passionate core of that life seem even more astonishing.

Michael Feingold is the chief theater critic of The Village Voice and literary adviser to Theater for a New Audience in New York. His translation of Schiller's "Mary Stuart" will be produced at the Pearl Theater this spring.

David Riggs: The World Of Christopher Marlowe

From Publishers Weekly

David Riggs: The World Of Christopher Marlowe

Riggs (Ben Jonson: A Life), an English professor at Stanford University, traces the life of Elizabethan poet, playwright and spy Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593), placing him in the context of the institutions that both fostered his keen intellect and reinforced his awareness of his lowly class origins (his father was a shoemaker). Riggs suggests that Marlowe, Shakespeare's great contemporary, author of Tamburlaine and Dr. Faustus, may have sought to overcome those origins through his unusual and dangerous career path. Working in the New Historicist vein most recently mined by Stephen Greenblatt in Will in the World, Riggs evokes the pedagogical preoccupations of Marlowe's school and university education, revealing layers of intricate detail in Marlowe's formation as a literary artist: his study and translation of Ovid, his innovations in blank verse, and the substance and reception of all of his plays and poetry. While downplaying Marlowe's disputed sexuality, Riggs pays careful attention to the homoerotic and homophobic aspects of his plays, most notably Edward II, considering each in its contemporary moral and political setting. Riggs concludes with fresh insights into the mysterious circumstances of Marlowe's violent death. This study balances close literary readings with lucidly presented historical context to give us a portrait of a brilliant but volatile enigma who shunned convention in favor of risk and marginality. 50 b&w illus.

From Booklist

David Riggs: The World Of Christopher Marlowe

*Starred Review* A biography of Shakespeare's greatest forebear in the Elizabethan theater must be the product of considerable grubbing and decoding. No portrait of Marlowe (1564-93) exists; he is referred to by several names (e.g., Morley, Merlin) that are spelled and, one would think, pronounced differently; and he had reasons to be untraceable, including the disesteem in which playwrights were held and his work-for-hire as a secret agent, maybe even a double agent, of the factions contending for power in England. Those contestants were the queen and high-church Protestants; the disestablished English Catholic Church and Catholic aristocrats at home and expatriate; and the rising Puritans, who could practically ally with the Catholics. Intelligent young lower-class men like Marlowe, the Cambridge scholarship-student son of an originally itinerant worker, functioned with enormous fluidity among those factions. Basically, Marlowe was a queen's man, but he was often arrested and ultimately murdered, Riggs shows, because he was suspected of being, or about to become, an atheist collaborator with the Catholics. His plays, as Riggs very persuasively parses them, argue that he was indeed atheist; with his reported behavior--rambunctious and blasphemous--they argue that he was antinomian and antiauthoritarian, too. Outstanding social history, detective work, literary analysis, and portrayal of a truly dangerous time and place--Elizabethan London. Ray Olson

A Brawler and a Spy

David Riggs – The World Of Christopher Marlowe

By John Simon.

Published: January 2, 2005

Pity the famous man born the same year as a more famous one: case in point Christopher Marlowe (1564-93) and William Shakespeare. At their simultaneous centenaries, Marlowe was shamefully shortchanged. It would be no less a shame if a recent popular biography of Shakespeare eclipsed David Riggs's worthy ''World of Christopher Marlowe.'' Kit and Will are a pair of equal deservers.

With praiseworthy modesty, Riggs calls his book ''The World,'' not ''The Life'' of his elusive subject. Elizabethan poets (the word ''playwright'' was not yet invented) leave far fewer traces than biographers might wish for. This holds for Shakespeare as much as for Marlowe, though Marlowe benefited from being a brawler and a spy: there is nothing like getting in trouble for getting you into the record books.

Christopher's father, a shoemaker in Canterbury, was the rare poor tradesman who was both literate and litigious. In his son, literacy was transmuted into literariness, litigiousness into falling afoul of the law. These were hard times, when hanging, beheading, even burning at the stake were often deemed insufficient punishment: the hanged man might be disemboweled while still alive; London Bridge was decorated with the heads of presumed traitors; and no one was safe, the male favorites of the Virgin Queen no more than the wives of her much-married father. The boy Christopher could watch from his window as prisoners were carted off to the gallows. At 8, he may well have been aware of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of Protestants across the Channel: several of his future plays contain massacres.

Between 1547 and 1558, the English state religion changed three times, making Catholics and Protestants equal-opportunity victims. As for anyone suspected of atheism, the sin of sins, he would soon be racked with more than doubt, what with screws literally put on. From the tortured, confessions could be readily extorted, but were they true? When fellow playwright Thomas Kyd was hauled in for questioning about an allegedly antireligious book found in the lodgings he shared with Kit Marlowe -- his roommate, bedmate and quite possibly sex-mate -- Kyd ratted on Kit to save his own neck. Was Marlowe an atheist and a homosexual? The circumstantial evidence is compelling, but proof is lacking.

More relevantly, Marlowe was poor. His six years of early schooling, like the next six in pursuit of the Cambridge B.A. and M.A., were almost all on scholarship. No picnics, any of them. ''Six-year-olds who did no work,'' Riggs writes, ''were said to be 'idle.' '' Kit, to be sure, was in school by then, taught for long daily hours little beyond parsing and memorizing Greek and Latin texts, to be beaten by often ignorant teachers if he balked. Even during play, the boys were compelled to use only Latin or Greek. No wonder their English suffered; during his lifetime, even in official documents, Marlowe was known as Marlow, Marly, Marley, Morely, Merly, Marlen, Marlyn, Marlin and Merling; his only preserved autograph signature reads Cristofer Marley.

Ironically, the future Christ-basher was a scholarship student at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. It was, for a poor youth, a grueling privilege. ''The rich,'' Riggs tells us, ''could roist it out with impunity. . . . The poor scholar could not wear gorgeous apparel, nor frequent riotous company, nor make the excuse that he was a gentleman.'' For him ''plain black gown'' and ''18-hour days, from 4 o'clock in the morning until 10 at night.'' He had a bit of free time on Sunday, but could go out in the evening only accompanied by a proctor. His plain wool clothing had to be, if not black, some other ''sad color''; he was forbidden ''long locks of hair'' and had to seem, in the words of his friend Thomas Nashe, ''mortifiedly religious.'' All this, Riggs points out, sharpened Marlowe's ''awareness of social inequality.'' In his plays, ''to dress above one's station is an infallible sign of social mobility.''

As Riggs stresses throughout, the leads and chief supporting characters were usually poor youths who rose high through physical or mental prowess, even if this flouted historical truth. Thus the real Tamburlaine had never been a poor shepherd, and Marlowe invented similarly lowly origins for the scholarly Dr. Georgius Faustus, Edward II's male lovers, and Peter Ramus, the illustrious scholar murdered in ''Massacre at Paris.''

Disputation -- rhetoric in which one had to argue both sides of an issue -- was a staple of the M.A. curriculum, and disputation drove Marlowe's dramatis personae and the drama of his own life and death. But Christopher learned more than that at Cambridge. In their sparsely furnished digs, ''like other members of the college, Marlowe and his roommates would have slept with one another.'' The contemporary attitude toward homosexuality was, to put it mildly, schizoid. ''Love between men was intrinsic to the humanist educational program. Yet the medieval-Christian impulse to demonize homosexual acts persisted regardless. . . . The law too was equivocal on this issue.''

And what of atheism? In a paper, Richard Baines, a former roommate turned enemy of Marlowe's, summed up for the Privy Council an atheist lecture Marlowe may have presented to Sir Walter Raleigh's group of alleged atheists, who, among other naughty things, spelled the name of God backward. The poet asserted that Moses was a juggler who could easily fool the gullible Jews, that Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest. Also that he, Marlowe, could come up pronto with a much better religion than the filthily written New Testament. Further, that St. John the Evangelist was Christ's bedfellow, who used him as the sinners of Sodom, and that they who loved not tobacco and boys were fools. Moreover, that he had as good a right to coin money as the queen.

These and similar charges leveled at Marlowe by several others are cited over and over again in Riggs's book, such repetitiousness being one of its few flaws. No doubt Marlowe's ideas about religion and hedonism were derived from the Cambridge curriculum. He had fallen for Ovid's sensual poetry (which he also translated) and the Epicurean philosophy of Lucretius, as well as for hard-nosed history from Polybius and Livy. Virgil was another influence, and it was in seeking an English measure to match the Latin hexameters that he adapted Sackville and Norton's iambic pentameter from their clumsy play ''Gorboduc'' and created the powerful yet flexible blank verse that Ben Jonson dubbed ''Marlowe's mighty line.''

When he left university and had to make a living, Marlowe gravitated toward espionage for the Privy Council and writing for the stage. The two were hardly antithetical. Many playwrights -- including George Gascoigne, Thomas Watson, Anthony Munday, Samuel Daniel and Ben Jonson -- espoused them both. As Riggs notes, ''The plots and counterplots of this era taught Marlowe that spies and scriptwriters had a lot in common.'' It was at the written request of the Privy Council that Marlowe got his M.A. -- by that time, he had often played hooky, mostly on the Council's behalf, employed as he was by them ''in matters touching the benefit of his country.'' The M.A., in turn, benefited Marlowe, and so, even more, did the theater.

Marlowe's ''base origins . . . and lack of any discernible gift for science and mathematics'' made him an unlikely candidate for political patronage; a clerical career was, of course, out of the question. ''The stage supplied Marlowe with an imaginative space commensurate with his intellectual reach'' and boundless ambition. His first major and most popular protagonist, Tamburlaine, proclaimed, ''I hold the Fates bound fast in iron chains / And with my hand turn fortune's wheel about.'' And again, ''Jove, viewing me in arms, looks pale and wan, / Fearing my power should pull him from the throne.'' Tamburlaine's followers, Riggs observes, ''take him for a god and he fulfills their expectations: in performing the role of Tamburlaine, Edward Alleyn became the first matinee idol in English drama.'' The first Tamburlaine play was such a hit that a sequel was called for. No other Elizabethan or Jacobean playwright -- not even Shakespeare or Jonson -- could claim a comparable crowd pleaser.

Still, playwrights were held in such low esteem that the published edition of the work did not mention Marlowe on its title page. For most authorities, the shoemaker's son had made scant progress by switching from cobbler to scribbler, merely trading lasts for lusts. As Lord Mayor Roe warned Archbishop Whitgift, playhouses were attracting ''great numbers of light and lewd-disposed persons as harlots, cutpurses, cozeners, pilferers and such like.'' It was for this antitheatrical disposition, as much as for outbreaks of the plague, that theaters could be closed, and Marlowe's income dwindle.

Christopher's career as man of the thea-ter, postulant for patronage, double agent dangerously embedded abroad and in England among Catholic recusants or Puritan zealots, is too complicated even for summarizing here. Riggs excels in showing how, in the character of Tamburlaine, Marlowe pursued his dream of power; in the amoral and conniving Jew Barabas, he indulged his rebellious and Machiavellian fantasies; and in Dr. Faustus, dramatized his social and sexual appetites. Then, switching from victimizer to victim, he identified with Edward II and his minions as a troubled homosexual. Always, though, the poor scholar was eventually empowered and aggrandized, albeit at the price of a sticky end. Marlowe the lyric poet also gets Riggs's attention, both as passionate shepherd whose invitation to love may be read as to boy or girl, and as the somewhat detached observer of ''Hero and Leander,'' a poem full of digressions to delay the sad ending (a strategy learned from Lucan, whom Marlowe also translated), even unto leaving the poem unfinished. Here, too, Marlowe's master theme pops up, denouncing the Fates: ''And to this day is every scholar poor; / Gross gold from them runs headlong to the boor.''

At long last, Marlowe became more thorn in the side than trump in the hands of the Privy Council, as party to a murder, accomplice in counterfeiting, repeated street fighter and atheist proselytizer. Upon failing to keep a bond compelling him to stay within striking distance of the court, he seems to have elicited Elizabeth's death sentence (''Prosecute it to the full''), so that Marlowe's murder was almost certainly not over a disputed tavern bill, but a staged fight among disreputable drinking companions, one of whom gave him the fatal stab in the eye. That the queen granted the killer a speedy pardon confirms the thesis of a political assassination, to which both Leslie Hotson and Charles Nicholl have devoted distinguished books.

If you want a concise but thorough critical study of Marlowe's place in world literature, consult ''The Overreacher'' by Harry Levin, one of two teachers Riggs acknowledges in a note. But if you want an exhaustive account of the life and times, Riggs is your man. You may applaud Marlowe with T. S. Eliot as the ''bard of torrential imagination,'' or deplore with Graham Greene his legacy of ''a few fine torsos, some mutilated marble'' (all his plays subsist in corrupt texts). But bear in mind: had Shakespeare, like Marlowe, died at 29, he would have stopped at ''Richard III,'' and achieved rather less than Marlowe.

John Simon is the theater critic of New York magazine and the music critic of The New Leader. Three volumes of his collected theater, film and music criticism will be published in May.

Next Page / Previous Page

Next Page / Previous Page